The Framework You Need for Successful Marketing Experimentation

If you’re a marketer, you need to be experimenting.

There’s no way around it.

When a company discourages (or doesn’t actively encourage) experimentation it leaves marketing vulnerable.

I’ve seen it happen a few times in my career.

Marketing is afraid to test new ideas or ask for more budget, so they repeat once-successful campaigns that have long reached the point of diminishing returns.

And here’s what happens:

- KPIs get watered down

- Leads are weak

- Marketing slowly loses credibility within the organization

Does that sound familiar?

I’ve written recently about experimentation as a key way to inspire new ideas, prove marketing ROI and generally avoid being a mediocre company.

A lack of experimentation within an organization usually goes hand-in-hand with a fear of failure. Company cultures that don’t view failure as an opportunity to learn will frown upon experimentation or even forbid it.

If this sounds like your company, my advice is to run like hell. Because if there’s one trait innovative companies share —including Google, Facebook, and Amazon—it’s that they embrace experimentation.

No marketer I know wants to work in this type of environment.

Get an experimentation framework that works

Even if you work in a culture of experimentation, you still need to find the time and creativity to test new ideas.

But most importantly, you need a systematic plan to run effective experiments and learn from them.

With a plan you can confidently and effectively:

- Test new creative ideas.

- Find new demand.

- Verify that new audiences are receptive.

- Maximize the value you get from every campaign.

You can finally bring a method to the madness.

Here’s how we do it.

Prefer to watch the video?

Develop your own framework

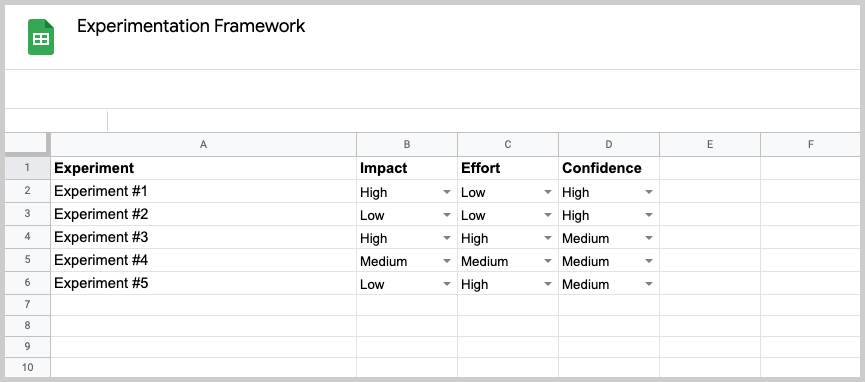

At Metadata, we’ve been leveraging a framework (originally built by Guillaume Cabane) for a few months to create and prioritize experiments and measure the results. One downside is that it’s, admittedly, fairly sophisticated.

So, if you’re just formulating an experimentation plan, walk before you run.

Create a spreadsheet where the only inputs are:

- Impact

- Effort

- Confidence

With the categories:

- High

- Medium

- Low

If you want to expand your experimentation framework further, here’s an Airtable framework template to get you started.

And each section below will give you tips and strategies for creating each part successfully.

1. Focus on your budget

Before you’re off to the races with experimentation ideas, you should understand the budget you have to experiment with and the demand and performance gaps you need to fill.

Your experimentation budget will depend on:

- Your total working budget.

- The percent of your goals your working budget will deliver.

Let’s say you know you can deliver a lead for $100 from your current channels and tactics. Last month your goal was 100 leads, and your budget was $10,000. You had enough budget to meet your goals using tried-and-true tactics.

However, this month your goals have changed to 120 leads, but your budget only went up by $1,000 to $11,000.

Now there’s a gap of 10 leads to make up.

You no longer can meet your goals using past tactics and performance. In this case, you would only spend, say, $9,000 on the traditional tactic to drive 90 leads, leaving a gap of 30 leads and $2,000. This is where experimentation comes in—you need to try new things to get your CPL down to $67 for those last 30 leads.

However, even if you have enough budget to meet your goals using tried-and-true tactics, you should still be experimenting. Because at any moment those tried-and-true tactics could bomb.

Try and optimize your current campaigns and use the dollars saved to do additional experimentation.

If you’re in this situation, try and reserve at least 10% of your budget for new experiments.

2. Gather your experimentation ideas

Start by brainstorming ideas and then consistently add new ideas to your list as they come up. You should also give others within your organization access to the list so they can add their own ideas.

If you’re looking for a few ideas to get started, try these out:

- Test new landing page headlines.

- Try out a brand new marketing channel (TikTok, YouTube, LinkedIn).

- Run a new set of Facebook Ads.

- Throw a digital event for your users/prospects.

- Sponsor a newsletter or podcast.

Ideas can be big as running a user event. Or as small as testing some ad copy and creative. The goal is to get in the mode of experimentation. After you have enough solid ideas down on paper, add data to help prioritize the experiments.

After you have your ideas, start to include data points such as:

- Effort – The difficulty level to build the experiment.

- Time – How long it will take to build and run.

- Impact – What the potential impact will be (in terms of dollars or primary KPIs).

- Confidence – Your confidence level of the experiment working.

- Revenue possibility – The revenue estimate for the experiment.

- Surface area – What part of the lifecycle it will affect: Acquisition? Pipeline? Retention?

When you do the math properly, the ideas that have the best mix of effort, impact, and confidence will float to the top— i.e. your “low-hanging fruit”.

From these data points, you’ll be able to create an ordered list of the experiments you should run.

3. Set up experiment timelines and KPIs

Next, assign the top priority experiments to sprints and begin building. When you build, build the most basic MVP (minimum viable product) possible so you can test and iterate the experiment without wasting time.

One of the biggest mistakes in experimentation is to try and build the perfect version the first time out.

Here’s the reality: a large percentage of your experiments may fail.

So it’s important to reach the right balance of quality and speed. Use your MVP to learn and decide if it’s an idea you want to formally expand.

Provide the budget and timeline so you know from the start how long you want the experiment to run before you have enough data to be satisfied.

You should also assign success and failure KPIs so you know if the experiment is beating or missing expectations. For instance, metrics to watch for an MVP would be CTR, CPL, and lead conversion.

While these are not the normal metrics for measuring marketing success, they’re a good indication that the experiment is resonating and should be rolled out more formally.

4. Assess the impact and what’s next

After an experiment has run its course, do a complete analysis of its impact and make a decision, usually one of the following:

- It performed great and should be an evergreen campaign that we build out even further and continue to optimize.

- It needs some tweaks and a retest.

- It just didn’t work…let’s get rid of it.

Make sure to absorb and track these learnings so you can build on what you learned and not repeat the same experiment twice. And keep a running list of insights you’ve learned through experimentation.

Start experimenting

Take the ideas with low effort and high impact and confidence and run them as your first experiments.

As you generate more ideas (and you will), add inputs such as the metrics it will affect and how long it will take to build and run. Keep building on it.

Sooner than you think, you’ll have enough data and ideas to run a well-oiled experimentation engine that’ll keep you a step ahead of your always-evolving audience.